Rasmussen and practical drift

Drift towards danger and the normalization of deviance

High-hazard activities rely on rules, procedures and standards to

specify safe ways of operating. These procedures, written by system

designers in collaboration with safety experts, attempt to anticipate

anomalous situations. However, regulations and procedures for work in

complex systems are always incomplete, and sharp-end staff must

sometimes deviate from the task as planned.The existence of a gap between work-as-imagined (WAI)

and work-as-done (WAD) is widely accepted today, thanks to the work of

several generations of researchers and experts in human

factors/ergonomics and cognitive systems engineering. The first

researchers to have taken a significant interest in this were from the

French-speaking “activity-oriented” school/tradition of ergonomics [Daniellou

2005], which paid a lot of attention to the real activity of

people in the workplace, unlike ergonomics research in most other

countries, which at the time was mostly concerned with anthropometrics

and workplace design issues. French ergonomists analyzed the difference

between travail prescrit and travail réalisé

(prescribed vs effective work) [Ombredane and Faverge 1955] and later

between tache and activité (the task and the activity)

[Leplat and Hoc

1983]. Early work on cognitive

systems engineering (human-machine interaction) analyzed the

difference between the system task description and the

cognitive tasks [Hollnagel and Woods 1983].

These deviations may be required by circumstances that

were not anticipated by the procedure’s authors, requiring frontline

workers to develop workarounds. Other deviations are due to workers

developing shortcuts and local optimizations which reduce their workload

or improve productivity [Dekker 2011].

Over time, this phenomenon leads to “the slow steady uncoupling of practice from written procedure” [Snook 2000]. Behaviour that is acquired in practice and is seen to “work” becomes “legitimized through unremarkable repetition”, as organizational theorist Snook writes (“it didn’t lead to an accident, so it must be OK”).

Pioneering safety researcher Jens Rasmussen identified a similar phenomenon which he called “drift to danger” [Rasmussen 1997], the:

systemic migration of organizational behavior toward accident under the influence of pressure toward cost-effectiveness in an aggressive, competing environment

Rasmussen represented the competing priorities and constraints that affect sociotechnical systems in his “migration model”, shown below. Any large system is subjected to multiple pressures: operations must be profitable, they must be safe, and workers’ workload must be feasible. People experiment within the space of possibilities formed by these constraints, as illustrated below:

if the system reduces output too much, it will fail economically and be shut down;

if the system workload increases too far, the burden on workers and equipment will be too great;

if the system moves too far in the direction of increasing risk, accidents will occur.

All organizations are affected by different pressures and

adaptive processes, which compete for attention, and lead to

migration or drift,It’s interesting to note (this was pointed out by

safety researcher Petter Almklov) that the Norwegian word for operations

is drift (for example, the operations department of a company

is called drift).

often towards situations with higher levels of risk.

Steps involved in drift to danger

This “drift into failure” tends to be a slow process, with multiple

steps which occur over an extended period. Each step is usually small so

can go unnoticed, and no significant problems are noticed until it’s too

late. Safety researcher Barry Turner refers to the concept of the

incubation period, during which latent errors

accumulate [Turner 1978].

NASA safety manager Herb Shivers uses the analogy of the boiling

frogThe fable of the boiling frog points out that if a frog

is dropped into a pot of boiling water, it will immediately attempt to

jump out. If however the frog is placed in warm water which is then

progressively heated, the frog will not perceive the danger and will be

cooked to death. (It seems that this fable is incorrect, and that a frog

will generally jump out of a slowly heating pot of water.)

[Shivers 2011] to

emphasize that when safety professionals notice that the surrounding

temperature seems to be increasing, they should search for a way to make

the environment correct rather than adjusting to the temperature or

ordering a cool drink.

Drift is not caused by people’s evil desires to generate accidents, or by lack of attention or of knowledge; it is a natural phenomenon that affects all types of systems.

Drift as a natural phenomenon

It’s important to note that the concept of drift to danger is different from the purposeful strategy of incrementalism or creeping normality, in which some actors decide on the end state that they wish to see appear, assess that it won’t be possible to get the system into that state immediately (for example due to resistance from other actors in the system), and break up the change into a large number of gradual steps, that they hope their opponents will not detect. Drift into failure is not the result of any particular person or group’s plan to generate an accident, but rather a byproduct of their adaptive behaviours.

The safe performance boundary is fuzzy and dynamic

In the figure above representing the space of possibilities, the safe performance boundary is clear-cut and easy to identify. However, in practice, the boundary is fuzzy and difficult to characterize in complex safety-critical systems. Accidents are generally not a simple on-off process, but are caused by unexpected combinations of events, non-linear interactions, incomplete understanding of complex processes, hubris and fatigue. They are also very rare events, so system operators have little information to point to indicating exactly where the line between safe and unsafe is located.

Furthermore, the safe performance boundary can move over time, in

response to outside events. This is a feature of adaptive

systems.Note that pretty much all large systems are adaptive,

because in an evolving environment, any system which does not adapt will

eventually fail and die.

For instance, major accidents tend to lead to a push that

(temporarily) increases safety margins, and the introduction of new

technologies can either increase or decrease the safety margin.

In most systems, movement towards the safe performance boundary is

slow and incremental. However, systems which exhibit both high

complexity and tight couplingThis distinction between loose and tight coupling was

first applied to the analysis of organizations by the famous

organizational theorist Karl Weick, in an analysis of the operation of

educational institutions [Weick 1976]. He suggested that the weak

influence of school and university bureaucracies on the work of faculty

is what allows these systems (“semi-organized anarchies”) to cope with

divergent interests held by its members. Weick later defined loose

coupling as a link between system elements which affect each other

“suddenly (rather than continuously), occasionally (rather than

constantly), negligibly (rather than significantly), indirectly (rather

than directly), and eventually (rather than immediately)” (quoted in

[Orton and Weick 1990], an article in

which he criticises research using this term as a “deceptively simple

bipolar notion” between autonomy and interdependence). Charles Perrow,

in analyzing the Three Mile Island accident, argues that tight coupling,

associated with interactive complexity, is one of the system features

that led to the accident [Perrow 1984].

between components (strong dependencies that propagate

effects in one component to other components quickly and in sometimes

unpredictable ways) can occasionally make large, unexpected “jumps”

towards the boundary, when the organizational slack (buffering ability)

which normally allows operational variability to be absorbed is suddenly

consumed. Richard Cook calls this sudden loss of operational slack

“going solid” [Cook and Rasmussen

2005]; the subsequent cascading effects can lead to system

failure and major accidents.

The drift into failure model highlights the importance of a system’s

history in explaining why people work as they do, what they believe is

important for safety, and which pressures can progressively erode

safety. The model helps see safety as a control

problem,And not just as a component reliability problem, where

you attempt to manage the number of failures. As Rasmussen pointed out,

the control system that generates safety is a multilevel one, starting

at the sharp end with the system operators and maintenance workers, and

including front-line managers, site managers, top-level company

executives, safety regulators and the legislators that define the social

licence to operate the hazardous system. The control system includes

both feed-forward (proactive) mechanisms such as risk analysis, and

feedback (reactive) mechanisms such as operational experience

feedback.

where the underlying dynamics are very slow but also very

powerful, and difficult to manage.

Related accidents

A number of significant accidents illustrate the concepts of drift into danger and normalization (or institutionalization) of deviance:

The Challenger space shuttle accident

in 1986 was caused, at a technical level, by the failure of O-rings in

the solid fuel booster rockets. The investigation into the accident

showed that these O-rings regularly sustained damage (erosion of the

joint material) which exceeded the level that was planned for during

rocket design, so engineers tracked the O-ring damage and the occasional

failures (damage occurred in fourteen of twenty-four prior flights).

Since the failures did not escalate to produce an accident, a feeling

grew that they were not dangerous, and managers approved “criticality 1

waivers” despite the design goal of zero joint failures. The launch day

was unusually cold, leading to worse than usual performance for the

O-rings, and eventually to their complete failure. A detailed analysis

of the organizational culture at NASA, undertaken by sociologist Diane

Vaughan after the accident, showed that people within NASA became so

much accustomed to an unplanned behaviour that they didn’t consider it

as deviant, despite the fact that they far exceeded their own basic

safety rules. This is the primary case study for Vaughan’s development

of the concept of normalization of deviance Normalization of deviance is the idea that people

working in an organization tend to become so accustomed to deviant

behaviour and rule violations that they don’t even “see” them any

longer, even when they are clearly not compatible with

official/prescribed practice and when the safety impacts are easy to

understand [Vaughan 1996].

It’s a negative form of social learning.

The Challenger space shuttle accident

in 1986 was caused, at a technical level, by the failure of O-rings in

the solid fuel booster rockets. The investigation into the accident

showed that these O-rings regularly sustained damage (erosion of the

joint material) which exceeded the level that was planned for during

rocket design, so engineers tracked the O-ring damage and the occasional

failures (damage occurred in fourteen of twenty-four prior flights).

Since the failures did not escalate to produce an accident, a feeling

grew that they were not dangerous, and managers approved “criticality 1

waivers” despite the design goal of zero joint failures. The launch day

was unusually cold, leading to worse than usual performance for the

O-rings, and eventually to their complete failure. A detailed analysis

of the organizational culture at NASA, undertaken by sociologist Diane

Vaughan after the accident, showed that people within NASA became so

much accustomed to an unplanned behaviour that they didn’t consider it

as deviant, despite the fact that they far exceeded their own basic

safety rules. This is the primary case study for Vaughan’s development

of the concept of normalization of deviance Normalization of deviance is the idea that people

working in an organization tend to become so accustomed to deviant

behaviour and rule violations that they don’t even “see” them any

longer, even when they are clearly not compatible with

official/prescribed practice and when the safety impacts are easy to

understand [Vaughan 1996].

It’s a negative form of social learning.

. Her work is significant in illustrating how a causal analysis can move beyond technical problems and individual decisions to explore the organizational structure, its culture and historical evolution.

- The Columbia space shuttle accident in 2003 was caused by foam breaking off the external fuel tank and hitting the shuttle during takeoff, damaging its thermal protection system. The shuttle burned up during re-entry into the earth’s atmosphere. Analysis of the accident by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board [CAIB 2003] showed that previous flights had also been affected by foam loss, without leading to catastrophic consequences. The investigation suggested that NASA had suffered from the same type of drift towards danger as prior to the Challenger accident 10 years earlier. Foam loss incidents were viewed as a maintenance issue, and not as a flight safety issue, despite the fact that foam loss was not an acceptable scenario according to shuttle design, and despite regular damage.

A 1994

friendly fire accident in which two U.S. Air Force F15 fighter jets

patrolling the no-fly zone over northern Iraq in the aftermath of the

Gulf War shot down two U.S. Army Black Hawk UH-60 helicopters is

documented by former military engineer and organizational theorist Scott

Snook in his book Friendly Fire [Snook 2000]. Following an operational

error made by the helicopter pilots, a partial failure of IFF

equipment,Identification, Friend or Foe (IFF) equipment is

designed to allow aircraft to identify whether other aircraft or

vehicles are “friendly” (belong to the same military coalition). Most

implementations are based on radio signals.

A 1994

friendly fire accident in which two U.S. Air Force F15 fighter jets

patrolling the no-fly zone over northern Iraq in the aftermath of the

Gulf War shot down two U.S. Army Black Hawk UH-60 helicopters is

documented by former military engineer and organizational theorist Scott

Snook in his book Friendly Fire [Snook 2000]. Following an operational

error made by the helicopter pilots, a partial failure of IFF

equipment,Identification, Friend or Foe (IFF) equipment is

designed to allow aircraft to identify whether other aircraft or

vehicles are “friendly” (belong to the same military coalition). Most

implementations are based on radio signals.

poor communication with air traffic controllers on a military AWACS aircraft, the F15 pilots misidentified the two helicopters as Iraqi Hinds, and fired missiles that killed all 26 peacekeepers aboard. The error was made more likely by poor communication between the fighter pilots, poor coordination between the different U.S. forces present in the zone and the dilution of responsibility across the different actors in the system.

The crash of cruise ship Costa Concordia, a 4800 person capacity modern

passenger liner, on an island close to the coast of Italy in 2012 (32

killed) after the ship captain intentionally deviated from the standard

course, taking the ship very close to shore in a manœuvre known as a

“ship’s salute”. The directors of the cruise company “not only

tolerated, but promoted and publicised the risky ship salutes off the

island of Giglio and other tourist sites as a convenient, effective

marketing tool”, according

to a criminal suit filed in the case. These salutes, greeting

inhabitants with the ship’s foghorn, were commonplace, and the mayor

of Giglio wrote to a captain of a Costa vessel to thank him for the

“unequalled spectacle”, which had become an “indispensable

tradition”.

The crash of cruise ship Costa Concordia, a 4800 person capacity modern

passenger liner, on an island close to the coast of Italy in 2012 (32

killed) after the ship captain intentionally deviated from the standard

course, taking the ship very close to shore in a manœuvre known as a

“ship’s salute”. The directors of the cruise company “not only

tolerated, but promoted and publicised the risky ship salutes off the

island of Giglio and other tourist sites as a convenient, effective

marketing tool”, according

to a criminal suit filed in the case. These salutes, greeting

inhabitants with the ship’s foghorn, were commonplace, and the mayor

of Giglio wrote to a captain of a Costa vessel to thank him for the

“unequalled spectacle”, which had become an “indispensable

tradition”.

Contributing factors

Factors that contribute to practical drift and the normalization of deviance:

- Production pressure or cost reductions overriding safety concerns,

with an increasing tolerance for

- shortcuts or “optimizations” that allow increased performance

- “temporary” violation of safety rules during periods of high workload

- circumvention or shunting of safety barriersFor example, fire doors slow down people’s travel

around their workplace, and are difficult to open due to their weight.

It is not uncommon when walking around industrial facilities to see fire

doors blocked in the open state, where they are totally ineffective in

slowing progression of a fire.

The absence of periodic reassessments of operational procedures to align them with system evolutions and the usual practices of sharp-end workers (involving a risk assessment when changes are made).

Excessively long and complex operational procedures. This is often caused by gradual accretion of extra checks and safeguards each time an incident analysis has identified a possible source of failure (“oh, we’ll ask the operators to check that the pressure isn’t above usual at this stage”), in particular when the underlying reason for the extra check is not explained to frontline staff.

Organizational barriers which prevent effective communication of critical safety information and stifle professional differences of opinion (“he’s a troublemaker”, or “not a team player”, or “doesn’t understand our way of doing things”).

Appearance of informal chain of command and decision-making processes that operate outside of the organization’s rules.

Confusion between reliability and safety, including reliance on past success as a substitute for sound engineering practices (“it worked last time, so even if it’s not quite compatible with our standards, it’s good enough”).

A “limit ourselves to compliance” mentality (“checklist safety”), in which only those safety innovations that are mandated by the regulator are implemented.

Insufficient oversight by the regulator, or regulators with insufficient authority to enforce change in certain areas.

A tendency to weigh operational ease/comfort/performance more than the restrictions which are often required for safe operation.

More guidance relevant to the process industry is available in a CCPS book titled Recognizing and Responding to Normalization of Deviance [CCPS 2018].

Criticism of the notion

Safety researcher/guru Sidney Dekker states [Dekker 2004, 133]:

Maintaining safety outcomes may be preceded by as many procedural deviations as accidents are.

According to this view, deviations from procedure (in particular when the procedures are poorly designed) may be necessary to cope with unusual conditions and specific characteristics of the working environment; they do not necessarily indicate that safety margins have been eroded. Dekker emphasizes the importance of hindsight bias: when you undertake an investigation to find the factors that contributed to an accident, it’s easy to unearth deviations from procedure and decide that they are causally related to the accident, though in practice they may have been commonplace and did not usually lead to bad outcomes.

Note however that procedural violations are only one component of drift to danger, which also refers to changes in people’s perceptions of risk, their priorities, decision-making, and interactions with other people and other organizations.

Safety researcher Erik Hollnagel makes a similar point [Hollnagel 2009]:

Performance variability may introduce a drift in the situation, but it is normally a drift to success, a gradual learning by people and social structures of how to handle the uncertainty, rather than a drift to failure.

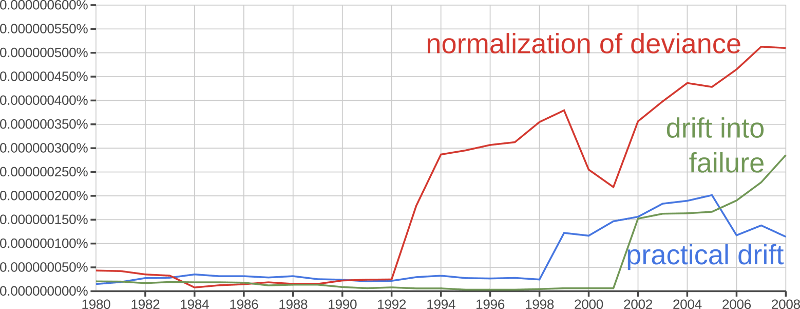

Interest over time

The figure below shows the frequency of the phrases “practical

drift”, “drift into failure” and “normalization of deviance” in printed

documents over the last few decades.Data provided by the Google Books ngram viewer.

Unfortunately, data more recent than 2008 is not available at the time

of writing.

This data suggests that the concept of normalization of deviance has gained more “intellectual traction” over recent decades than the related concept of practical drift. This is a little unfortunate in the author’s opinion, because practical drift is a more general concept, is probably more often encountered in practice, and (being situated at a broader organizational level) provides more levers for intervention to limit the phenomenon.

Conclusion

Rasmussen’s migration model illustrates that small optimizations and adaptations can accumulate over time, taking the system far from its initial design parameters. If there is no counterweight to this “practical drift” from operations staff who are alert to the possibility and the dangers of the normalization of deviance, from the safety function, or from an effective regulator, systems are likely to drift towards catastrophe.

Photo credits: Challenger space shuttle by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, CC BY-NC licence; Black Hawk helicopter by Jason Mrachina, CC NC-ND licence; Costa Concordia by Dan H, CC BY-NC licence.

References

CAIB. 2003. Report of the Columbia accident investigation board. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/remembering-columbia-sts-107/.

CCPS. 2018. Recognizing and responding to normalization of deviance. Wiley,

Cook, Richard I., and Jens Rasmussen. 2005. “Going solid”: A model of system dynamics and consequences for patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety 14:130–134. [Sci-Hub 🔑].

Daniellou, François. 2005. The French-speaking ergonomists’ approach to work activity: Cross-influences of field intervention and conceptual models. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 6(5):409–427. [Sci-Hub 🔑].

Dekker, Sidney W. 2004. Ten questions about human error: A new view of human factors and system safety. CRC Press,

Dekker, Sidney W. 2011. Drift into failure: From hunting broken components to understanding complex systems. Ashgate,

Hollnagel, Erik. 2009. The four cornerstones of resilience engineering. In Resilience Engineering Perspectives, Volume 2: Preparation and Restoration, edited by Christopher P. Nemeth, Erik Hollnagel, and Sidney Dekker, 117–134. Ashgate.

Hollnagel, Erik, and David D. Woods. 1983. Cognitive systems engineering: New wine in new bottles. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 18(6):583–600. [Sci-Hub 🔑].

Leplat, Jacques, and Jean-Michel Hoc. 1983. Tache et activité dans l’analyse psychologique des situations. Cahiers de Psychologie Cognitive 3(1):49–63.

Ombredane, André, and Jean-Marie Faverge. 1955. L’analyse du travail: Facteur d’économie humaine et de productivité. PUF.

Orton, J. Douglas, and Karl E. Weick. 1990. Loosely coupled systems: A reconceptualization. The Academy of Management Review 15(2):203–223. [Sci-Hub 🔑].

Perrow, Charles. 1984. Normal accidents: Living with high-risk technologies. New York. Basic Books,

Rasmussen, Jens. 1997. Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Safety Science 27(2):183–213. [Sci-Hub 🔑].

Shivers, C. Herbert. 2011. The parable of the boiled system safety professional: Drift to failure. In Proceedings of the 29th International System Safety Conference. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20110015770.

Snook, Scott A. 2000. Friendly fire: The accidental shootdown of US Black Hawks over northern Iraq. Princeton, USA. Princeton University Press,

Turner, Barry A. 1978. Man-made disasters. London. Wykeham Publications,

Vaughan, Diane. 1996. The Challenger launch decision: Risky technology, culture and deviance at NASA. Chicago. University of Chicago Press,

Weick, Karl E. 1976. Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quaterly 21(1):1–19. [Sci-Hub 🔑].

Published:

Last updated: